The Edmonton Hunger March of 1932

2:55 P.M., Tuesday, December 20th, 1932.

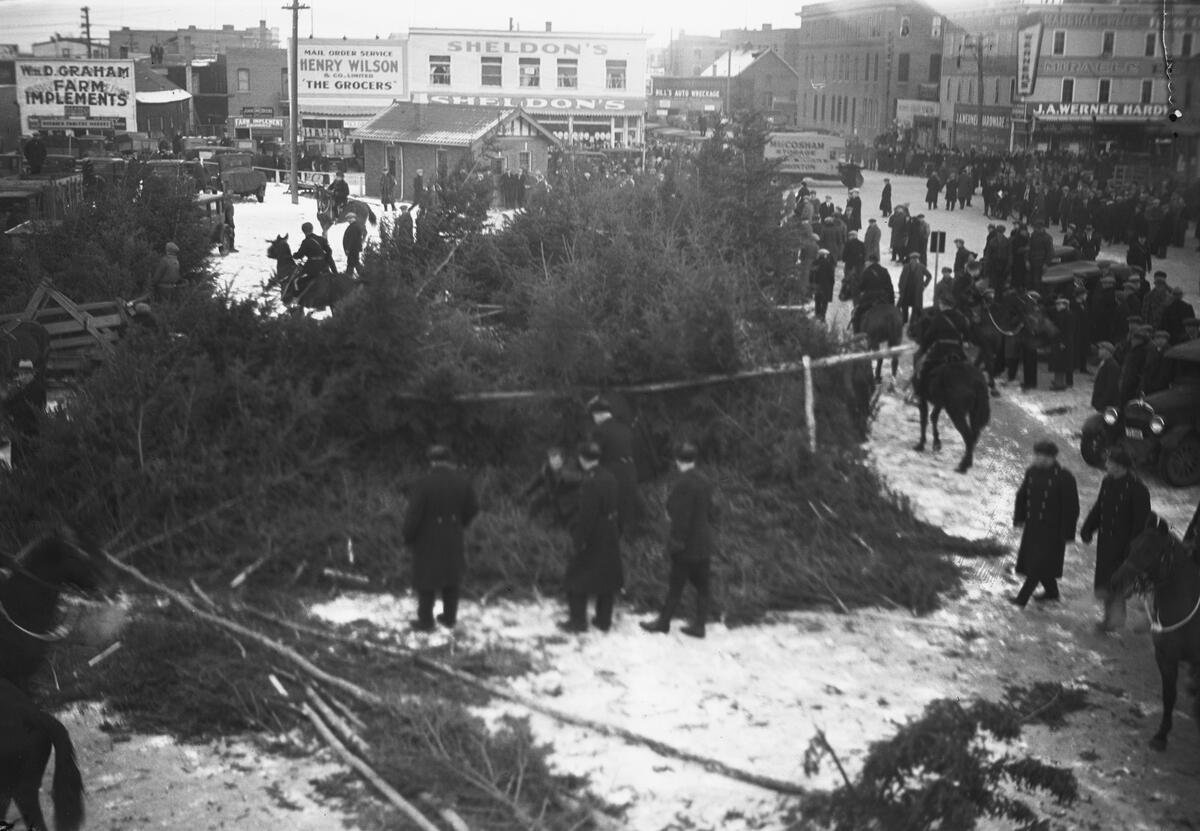

Tensions grew at Edmonton’s Market Square. On one side were the combined forces of the Edmonton Police Department (E.P.D.) and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (R.C.M.P.). One-hundred-and-fifty constables surrounded the gravel lot all intent on enforcing a parade ban issued by City Council, Edmonton’s Chief Constable, and the Premier of Alberta. On the other side was the banned parade, a crowd between four and ten-thousand strong. Albertans of every shape and size made up their ranks — Left-wing beliefs, destitution, and a desire for change linked them.

Rallying the rabble from atop a parked Ford was thirty-five year-old Andrew Irvine. Once a farm labourer, Irvine became radicalized at the Great Depression’s onset — with no chance of work, he was unable to support his dying mother. Expelled from the Unemployed Ex-Servicemen’s Association for his increasingly militant beliefs, the lean Great War veteran took to heading the provincial chapter of the National Unemployed Workers’ Association, a communist organization which co-ordinated agitation among the nation’s jobless. Now, grey eyes squinted and mousy hair jostled, the short-statured Red spit words like a preacher to the crowd of thousands.

“There is no law in Canada that can prevent us from peacefully walking along the sidewalk!”

A roar erupted.

“We don’t want violence and I want you to refrain from violence,” Irvine pleaded. “If there’s any violence, let it be the police who start it” he hissed, pointing towards the line of E.P.D. constables along 102nd Avenue.

“They are waiting and they will use agents to try and start trouble, but don’t be intimidated! If any trouble is started let the blame rest with them!”

A sharp whack echoed out as a policeman thrust a truncheon into his gloved hand. Another constable followed suit. And another. The intimidating, muffled roar of leather-on-leather took over the square.

“We have a constitutional right to use the King’s highway to petition parliament!”[1] Irvine shouted, pounding a fist into his palm. “So come on, boys! If you want a parade, let’s go!”

The protesters took their first step. As the marchers moved south towards 101A Avenue they unfurled banners and raised signs into an overcast sky.

“Workers of the World, Unite!” they rallied.

When the crowd reached 101A Avenue they made a sharp turn west. Passing the City Market Building, they neared the intersection of 101A and 100th Street. There they intended to turn south and continue towards Jasper Avenue. They came to an unexpected halt as a uniformed, metallic stomp deafened everything.

Enthralled spectators, who had built a chaotic wall around the column, parted revealing twenty-two horse-drawn members of the R.C.M.P. riding in a knee-to-knee phalanx. Thomas H. Irvine [2] commanded them. A balding, big-nosed Brit, he was promoted not four days before to Acting-Superintendent of the R.C.M.P.’s G-Division. He watched on with a steely gaze as his men met the marchers near the intersection.

The Mounties came to a halt, and both sides stared at each other passively for a moment. Neither flinched, each resolute.

The marchers made up their minds — another step.

Without a second’s hesitation the Superintendent’s voice boomed; “Walk march!”[3]

Before the order had a chance to dissipate in the cool winter’s air, the Mounties pushed themselves forward. As the defiant line of demonstrators quickly faltered, Superintendent Irvine blew into his whistle. From the vacated Market Building echoed steps of thirty on-foot members of the R.C.M.P.’s K-Division coming to assist, truncheons swinging. The E.P.D. followed and pushed down into the square from 102nd Avenue. Pandemonium ensued.

Alberta’s destitute, panicked and afraid, picked up what they could to defend themselves: rocks from the gravel square; branches from on-sale Christmas trees; billets of firewood.

At 3:05 P.M. they clashed with police.

The Fehr Family, shoeless and foodless, pictured outside of Edmonton’s Central Police Station in 1934. This iconic photo — “probably the most famous to come out of [Canada during] the Great Depression” — is emblematic of the hardship facing many during that era’s darkest days.

Glenbow Archives Photo No. ND-3-6742

THE CONDITIONS of 1932

Before proceeding it is worth assessing the conditions that lead to a mass uprising. In Edmonton’s case, the Hunger March of 1932 is inextricably linked to the material and socio-economic conditions of Alberta during the Great Depression.

Following the stock market crash of October 1929, Canada’s gross national product fell seventy-five percent. Personal income in Alberta fell by forty-eight percent, and farm wages by fifty. The value of farmland itself plummeted by forty percent, while nationwide unemployment rose to thirty. Everywhere dust hounded crops and fires plagued towns. As H. Blair Neatby explained:

“The [Depression’s] impact, however, was greatest on two large groups in Canada: the unemployed and the prairie farmer. For both of these groups the depression was a tragic experience which tested their fortitude and shattered the comfortable illusions about Canadian society and Canadian institutions… The 1930s was thus more than a period of economic recession. It was also a time when Canadians seriously, and almost for the first time, began to analyze the structure of their society.”

And yet, despite these pressures and increasingly strident calls for change, nothing was done. Cities, provinces, the Dominion: each squabbled, passing the buck from one party to the other. No-one wanted the responsibility — and price-tag — associated with Depression-relief.

Problems with relief delivery stemmed from Canada’s archaic constitution. Pierre Burton posited that it “divided responsibility in such a way that the destitute could not rely on help from anyone.” Ottawa, under Prime Ministers Mackenzie King and Richard Bedford Bennett, washed their hands of the matter, and standing on the rock of the British North America Act argued it was the provinces’ responsibility to help their needy.

The provinces and municipalities of Canada, still largely agrarian, could do little on their own. While help did come from the Dominion in time, it was too little, too late for most. The Bennett Government’s Unemployment Relief Act supplied $20,000,000 in assistance for the unemployed. Four-fifths of that money would cover up to twenty-five percent of any make-work project’s cost, to be given out to any municipality that could prove it had a scheme that could create jobs. The last fifth went towards direct relief, much of it handled by private charities and municipal relief departments.

The pittance given to direct relief is telling. A persistent belief existed among the upper-classes that too much aid would inevitably turn a population lazy. Canada’s aid system, which had its legal basis in Britain’s Nineteenth-Century Poor Laws, reflected this. For the government the way doling out help sought to make aid so denigrating as to force the public to stay away. Not that it was hard — overcoming the stigma of being a “reliefer” stopped many from even walking into the aid office to begin with. Compounding matters was that local Special Relief Departments did not seek out needy cases, instead, Burton continued, “expecting the unemployed to make application for relief of their own accord” knowing they would not. If you did go through with it, expect a visit from a relief official. The law permitted them to rifle through an applicant’s home. If an agent found anything costly — a telephone, a sole electric appliance, liquor, a beater of a car no matter how old — prepare to be disqualified.

In spite of the Dominion’s efforts, or lack thereof, one-tenth of Canadians, some 1,357,262 people, were on direct relief by December 1932. Another third required intermittent government-subsidized relief. In Edmonton alone, the City’s Special Relief Department provided aid, on average, to 2,200 families each month across the Greater Edmonton Area that year.

Inevitably, these conditions birthed scathing critiques of capitalism and many sought out alternative systems. The Left — trade unionists, labourites, socialists, and communists — saw the biggest upswell in popular political support. Anne Woywitka wrote:

“As the depression deepened, so did bitterness and resentment. The unemployed joined the ranks of the Single Unemployed Workers Association, the Relief Camp Workers Union, and the C.C.F. [Co-operative Commonwealth Federation] Party. The Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Association also stood behind its members. Others became members of the Communist Party of Canada which took a vociferous lead in their demands for help for the needy.”

The Communist Party of Canada’s Workers’ Unity League (W.U.L.) became this era’s most significant player.[4] Formed in June 1929, the W.U.L. hoped to combat the lethargy of Canada’s entrenched unions with radical action and a revolutionary voice. Resource workers and unskilled labourers who had previously been left out of the mainstream trade union movement were the W.U.L.’s primary targets, however, they also exerted considerable effort organizing among the unemployed. In doing so, the Unity League became the only trade group willing to actively mobilize the jobless, and in stepping into this vacuum, Lorne Brown contended, the W.U.L. allowed the downtrodden to be “able and willing to employ the militant tactics necessitated by the task at hand.”

Leveraging the Communist Party’s Canada-wide network of activists and resources, the League produced a national political movement with “a specific, positive and realistic programme” demanding work, wages, food, and homes, with public relief “under dignified conditions.” In particular, the League’s adjunct, the National Unemployed Workers’ Association, campaigned, Jaroslav Petryshyn wrote, “for programmes of immediate relief for all unemployed to be paid from municipal, provincial, and federal funds, insurance for all workers against unemployment, no disqualification from relief because of a refusal to accept a pay cut or work below union rates, and no eviction of unemployed from their homes because of non-payment of rent.”

By late-1932, estimates placed the W.U.L. at 21,253 members across various associated unions and groups. Its revolutionary zeal and proletarian character attracted many, no doubt, if, as Bill Waiser argued, “only for the simple reason that the Communists held out the prospect of hope in place of growing despair.” Despite this, the W.U.L.’s status as a federation of unions and not a union per se hindered its efforts.

Unable to engage in collective bargaining on a national-level, and with no contacts in local, provincial, or federal governments, the W.U.L. turned to new, imaginative forms of action to expose their message. Sit-ins, mass cross-union protest demonstrations, and the presentation of petitions and delegations to elected officials became commonplace. Further, in-lieu of traditional union resources, the League developed alliances with sympathetic organizations, such as farm and labour co-operatives, church groups, and women’s leagues for help fundraising, lodging, and providing food.

Two other noteworthy organizations joined the Workers’ League. One was the Worker’s rural contemporaries, the Farmers’ Unity League (F.U.L.). Established in 1930, the F.U.L.’s aim, David Monod writes, “was parity prices and protection from seizures and foreclosures of farm lands, machinery and cattle by banks, mortgage companies, and machinery dealers.” Other demands included free hospitals and medicine, a guaranteed minimum income, and non-contributory social insurance and old age pensions for all farmers and farmhands.[5]

The Canadian Labour Defence League (C.L.D.L.) was the other. Formed in 1925 as International Red Aid’s Canadian-affiliate, the C.L.D.L. provided, according to their constitution, “legal defence for all workers prosecuted for expressions of opinion or working class activity,” in addition to “material and moral support for all working class prisoners,” and “the families and dependents of such prisoners.” By December 1932, they counted 350 branches and 17,000 members in their ranks.

Edmonton’s Hunger March was partly planned in these two buildings: the Workers’ International Relief headquarters (left) and Ukrainian Labour Temple (right). Police raided both in the lead up to, and aftermath of, the demonstration.

Provincial Archives of Alberta Photo No. 70-R0124-03 & G.3078, respectively.

The Lead Up

Beginning in October 1932, the W.U.L., F.U.L., and C.L.D.L. began planning an Edmonton-based hunger march — a form of unemployment demonstration meant to underline the starving conditions of the working-poor. The three leagues hoped that by creating a “united front” between the rural and urban proletariat for the first time they could show the powers-that-be that “the interests of the Worker and Farmer are one and the same thing.” “Why has this never been done before?” a communist-produced booklet later asked. “The answer is very simple. Those in power know and have known for a long time, that the moment Farmers and Workers unite together for a real struggle against any further exploration, marks the beginning of the end for them.”

The leagues created the Central Hunger March Committee. Led by Charles Stewart, August Popin, and Andrew Irvine, the Committee aimed to direct efforts and seek assistance from other communist, labour, trades, and church groups. Soon joining them was the Unemployed Married Men’s Association, Ukrainian Labour-Farm Temple Association (U.L.F.T.A.), and Workers’ International Relief (W.I.R.), among fourteen other such groups.

The Committee’s operation entered around three buildings in Edmonton’s Boyle-Street neighbourhood. Workers’ International Relief occupied one, an aging Foursquare home located at 9639 104th Avenue. The U.L.F.T.A. and their hall, located at 96th Street and 106A Avenue, housed out-of-town workers — the Young Communist League occupied a neighbouring church. Lastly was Jasper Avenue’s Gem Theatre, which provided a rallying place for sympathetic speakers.

The Hunger March Committee settled on a plan. They were to meet in market square and then march from there to the Legislative Building to meet Premier Brownlee and air their grievances. The choice of Market Square was obvious, Kathryn Chase Merrett contended, thanks to “its central location, its civic associations, and the flexibility of its open spaces [which had] made it a favourite martialling ground for parades and an occasional site for special events and demonstrations.”

The Committee expected thousands from across the province to attend, making Edmonton’s Hunger March a truly Albertan demonstration. Cognizant of the state’s position on Left-wing protests and the slew of charges that would inevitably follow such a demonstration, the C.L.D.L. preemptively threw themselves into soliciting donations for a bail fund in addition to supplying billeting options for travellers. Local farmers, meanwhile, handily answered the W.I.R.’s request to provide food. Locals provided the marchers with beef, turkeys, potatoes, flour, milk, cream, and butter, and by December 19th, International Relief had enough food to sustain 3,500 men for five days, in addition to municipal food-tickets.

Despite their revolutionary fervour and anti-establishment rhetoric, the March Committee attempted to present a friendly face and pursued their requisite parade permit through legal channels. When a delegation approached Edmonton City Council, Mayor Daniel Kennedy Knott, a Labourite, equivocated. “The threat of ‘a bloody battle’ didn’t move him,” Fred Cleverly explained. “Neither did the remarks of one alderman that a no-parade policy was ‘dangerously anti-social and stupid.’”

Knott’s rebuke is interesting in retrospect, least of all for who he did allow to parade; the Ku Klux Klan. At multiple points during his tenure, Knott’s City Council directly permitted the Klan to organize cross-burnings throughout Edmonton. The fact they pledged their support to the Mayor during his 1932 re-election campaign likely played no small part.[6] When pressed on this double-standard, Knott would only respond: “If the Premier is agreeable, the [police] chief will grant a permit.” In saying that, the Mayor knew full-well that Alberta Premier John E. Brownlee would not agree.

Brownlee, leader of the moderately Left-wing, social-democratic United Farmers of Alberta government, revealed his paranoia of a populist uprising as protests grew in number the two years prior. In May 1931, when he summoned Alberta’s mayors to the Legislature, some 500 demonstrators showed up; he ordered police to read the Riot Act. That same year protesters crowded Edmonton’s Civic Block demanding food tickets. While City-officials resolved the situation, he nevertheless called in the cavalry. Forty-three troopers from Lord Strathcona’s Horse, equipped with steel helmets, rifles, and Hotchkiss machine guns, travelled from Calgary to Edmonton.

This demonstration would be no different, and on December 5th, Brownlee handed down his ruling; a resounding no. “Any instance on the part of the agitators in carrying out the plan will be construed as a challenge to constituted authority and will be dealt with as such,” he proclaimed. Edmonton’s Chief Constable, Arthur Graham Shute, formally affirmed Brownlee’s decision on December 9th.

But the City’s and Province’s threats did not deter Alberta’s working class — it emboldened them. Rock Sudworth, a Blairmore communist, spoke for hundreds when he “declared that the only thing that would prevent him from getting to Edmonton would be a bullet through his body.” The March Committee itself was wholly unperturbed. Their internal estimates revealed that some 5,000 to 10,000 Albertans hoped to attend. They would still meet at Market Square at their planned date and at their planned time, it was decided. If they could not march, then they could still be heard.

Premier Brownlee soon called for assistance from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who agreed to commit fifty-two constables.[7] Together with the Edmonton Police Department, the R.C.M.P. surveyed Market Square for the optimal placement of their men, set up a machine gun nearby, and, as Andrea Hasenbank wrote, established a group of “‘twenty-five special men’ paid out of a secret service budget” to infiltrate March Committee meetings.

Edmonton Police Department Special Detective Andrew Wilchinski was at the forefront of these efforts. A Galician [8] immigrant, Wilchinski came to Canada in 1902, settling in Winnipeg where he married in 1903. Before moving west to Edmonton in 1912, he was associated with the R.C.M.P. as special instigator and interpreter. Both the Mounties and E.P.D. considered him an especially “valuable man… [for] investigations concerning foreign elements” due to his ability to speak Ukrainian.

Joining Wilchinski was R.C.M.P. Constables Jacob Tatko and Albert Harold Philip Keeler. For two weeks the three infiltrated meetings put on by the Hunger March Committee and its constituent organizations — Wilchinski directed his efforts towards those orchestrated by the C.L.D.L. while Tatko and Keeler bummed around with the Young Pioneers. Together the officers collected pamphlets, complied estimates of the marchers’ numbers, and built lists of Committee leaders and prominent speakers.

John Corrigan [9] caught the three’s attention immediately. A young Penholdian representative of the Farmers’ Unity League, Corrigan proved a natural orator and rallied hundreds with his “moderate” but inflaming rhetoric — Wilchinski begrudgingly admitted he “nearly succumbed” to the speaker’s declamations. At two separate meetings prior to the March, Corporal Keeler recalled Corigian warning marchers that “Primer Brownlee is going to use force and that the unemployed must do likewise,” “made references of a slurring nature against ‘police thugs,’ ‘Brownlee,’ and ‘Knott’, and urged the crowd to stand behind their leaders and battle for their rights.”

Yet, Hasenbank argued that for all their effort little came from the constabulary’s attempts at subterfuge. She drew attention to Detective Wilchinski in particular, and described him as something of an inept figure. In addition to his continued “misreadings of the radicals,” Wilchinski, in a series of reports made to Chief Constable Shute, “submits a poster covered with shorthand notation that he cannot decipher, as well as reports of speeches given in foreign languages that he cannot understand, or at least does not translate…”

Elsewhere, both police departments attempted to establish roadblocks to prevent more marchers from reaching Edmonton — their success here was equally dubious. Patrick Lenihan [10], a Calgary communist on his way home from the Fort Saskatchewan Penitentiary, recalled:

“We ran into a police barricade about 50 miles out of Edmonton. And here are the police on the highway and they’re searching cars because there were all kinds of organizers out amongst the farmers. Young men and old men, all kinds of organizers out organizing and bringing people in for the March. They were trying to catch some of them. And who did they stop? They stopped us. We were a suspicious looking bunch. And we told them we’d just come out of prison and who we were. And they let us go.

Ben Swanky, then a member of the Young Communist League, had similar memories. He once laughed that “the farmers came in during the night on the side roads.” Officials themselves admitted to the Edmonton Bulletin that “truckloads of hunger marchers have been filtering through the lines.” Some 400 arrived in Edmonton on one weekend alone, while on December 18th another 231 men followed. 427 Vegreville-area farmers soon joined them.

By December 19th the E.P.D. had scraped together a seventy-five man crowd control unit — an impressive feat given that in 1931 the Department consisted of only eighty-eight people on staff, all-ranks. That day Chief Shute ordered all hardware stores near the Square closed and their wares locked up so as to prevent their use as weapons if a riot broke out. Two police raids, one against the Workers’ International Relief headquarters and Ukrainian Labour Temple, subsequently followed. “The R.C.M.P. and the local police,” a communist publication later declared, searched “for arms and ammunition. None were found. The demonstrators had not come to shoot, but to see the premier.” [Bolding theirs.]

Again, the state’s reaction strengthened the marchers’ resolve, and on Tuesday, December 20th, 1932, Alberta’s destitute funnelled into Market Square with their heads held high. The Edmonton Hunger March officially began at 1:30 P.M. Demonstrators sung ‘The Internationale’ and “for more than an hour… heard increasingly strident appeals from their Communist leaders.” Following Andrew Irvine’s plea to carry on with their parade, they set off at 3:00 P.M. — five minuets later became engaged in the fight of their lives.

THE MEELE

For eight whole minutes the marchers and police bludgeoned each other. Cops smacked truncheons against flesh, demonstrators hurled rocks, and horses trampled those attempting to flee. The Edmonton Journal described:

“Several of the demonstrators fell to the pavement under well-directed blows from night sticks. At one time four of the marchers were lying on the ground, but only one needed assistance as he walked away… Several of those injured by blows from the police clubs hurried over to the McLeod Building with blood streaming down their faces to get medical attention… Frank Hyduk of Ranfurly was one who received a bad cut on the forehead. It was found on examination by Dr. Clyde MacDonald, that this man had a severed artery.”

An equal number of spectators to paraders had gathered to watch the protest. They stared helplessly until the marchers’ line faltered. When they dispersed, many strikers fled into the crowds looking for an out — the police followed in tow. As the constabulary’s ranks swept through the rabble, innocent bystanders tried to make way or take off. Soon it became “impossible to distinguish citizenry from the demonstrators.” Marchers and average Edmontonians alike became targets, and one citizen, Reg Healy, suffered a serious wound to the side of his head — he asserted that “he was merely watching the fight when he was cracked by police billies.”

“The Feelings of a By-stander on Bloody Tuesday,” later published in a Canadian Labour Defence League pamphlet, described the scene thusly:

“Have you ever been confronted by a rearing, maddened horse? Have you ever been attacked by a shouting policeman? Have you ever tried to force your way through a roaring, booing crowd of people with panic pressing in on you from every side, and the sound of deafening police billies pounding on your eardrums? I was standing on the sidewalk watching the police and waiting for the marchers when a sudden, horror filled cry swept through the crowd. ‘Watch out! The horses!’ Hemmed in by buildings, escape impossible, men, women, and children were ruthlessly ridden down.”[11]

Those who could, took shelter in the Market’s Fish Building. Some climbed atop parked cars to escape the brawl. Others pushed “automobiles away from the curb in the hope of breaking up [the R.C.M.P.’s] charge.”

The Mounties made several passes through the crowd, as E.P.D. and K-Division constables cudgelled others on foot, and some dismounted their horses to chase fleeing marchers. Clare Botsford remembered that some “people ran for shelter in the pyramids of Christmas trees that were on sale, and the clubbing went on, inside the shelter of these trees… Some of it you saw, some of it you heard, but certainly, a lot of people were injured…” “You never forget the sound of heads being clubbed… to this day I sort of get a little tremble in the lip when I think about it.”

Some of the marchers who managed to escape clambered atop the Market Building and hailed “a rain of stones and brickbats” at policemen below. One R.C.M.P. trooper took a rock to the face, and the E.P.D. sent four plainclothesmen to clear the roof. “Coming from behind they took the stone-throwers by surprise and wielding their billies with deadly accuracy they soon cleared the roof…”

But the marchers did not give in. Others, still in the Square, endeavoured to reform their line near the Market Building. “Police officers saw the attempt and troopers and foot police charged again,” the Bulletin wrote. Horses threw three paraders into the ground as others tried to flee.

The Bulletin asserted that a “mob spirt” overcame bystanders who “milled and surged around the police, hampering their efforts to get the streets cleared.” The R.C.M.P. soon had to pull back to the intersection of 100th Street and 101A Avenue to reestablish their phalanx. Demonstrators and onlookers enveloped them, chucking rocks and catcalls all the while. City police intervened to prevent the angry crowd from dragging the Mounties off their steeds.

As the violence mounted, and as the police readied themselves for another pass through the crowds, a shot echoed out. Panicked screams and desperate glances gave way to silence as both sides desperately looked for the shooter. Was it the Mounties’ machine gun? Again the crowd parted, and revealed an automobile — its owner, trying to escape the frenzy, caused the car’s engine to backfire. Cops and onlookers alike exchanged a brief bout of nervous laughter, and soon after tensions dissipated.

By 3:15 P.M. the worst of the fighting had died down, although sporadic brawls continued until 4:30 P.M. Chief Constable Shute later described the riot as “the wildest disorder in the city’s history.” Somehow no-one died, and excluding cuts and bruises, no-one grievously injured.

THE MEETING & Raid

Just as the melee at Market Square reached its apex, a delegation from the Hunger March Committee reached the Legislature Building. Hearing reports of the growing tensions, Premier Brownlee welcomed a group of marchers to his office, despite reservations. Representing the destitute was Alec Miller, an unemployed baker, John Corrigian, the fiery speaker, and G.H. Salter, a farmer, among a handful of others. Joining the Premier was Attorney-General John F. Lymburn and Alberta Provincial Treasurer Richard G. Reid.

The delegation took a seat and Brownlee told them to speak their minds. Describing their demands, the Journal said;

“There was, for instance, a request that the government pay to all farm youths of 16 years and over, $400 per year for support. The one item alone was at once seen to represent $4,000,000 or more annually, but the total cost of the platform had been not computed by the United Fronters. Among other demands were the following: Unemployment insurance at the expense of the state; a minimum of $15 cash per week to be paid to all married couples and $2.50 per additional for each dependent; any work to be provided to be at trade union wages, with a minimum of 50 cents per hour; abolition of labour camps; free medical and dental treatment; free rent, fuel, light, and water; free school supplies and clothing; exemption from all taxation for those earning $100 or less, cancellation of all debts for farmers; free medical care and education for rural people; no seizures of any kind for taxes; no evictions or foreclosures.”

The Premier proved wholly unsympathetic. “Are you hungry?” he asked one of the farmers. “No, I’m not hungry,” the man responded. “And you aren’t wanting clothes, are you? You are better dressed than many young men who come to my office.” “No. I’m not asking for clothes,” the farmer again answered. “What I am here for—” Brownlee cut him off. “How did you come to the city?” “In my car,” the man dryly replied.

Brownlee, a former lawyer, leaned back into his seat as if he had wormed out a confession. “Look,” he said, “the demands presented are utterly beyond the ability of the provincial government, even if they are all just or right. Further, let us not pretend Communist propaganda is not behind most of them. These same requests have been presented multiple times over the past two or three years by folks like you.” He concluded, the Journal wrote, by telling the marchers “what the Alberta government is undertaking in the way of unemployment relief and in meeting the debtor and creditor situation throughout the province.”

By then winter’s early darkness fell. Brownlee got up and wished them the best. The marchers reciprocated and peacefully left. Without looking back they returned to the Labour Temple. Their calm attitudes did not hide that they were throughly unimpressed. They were not naive enough to assume all their demands would be met, however, even reasonable suggestions such as a minimum for struggling married couples and free school supplies for suffering families, were opposed outright.

Sitting there that night unsatisfied, Edmonton’s Hunger March Committee began drafting plans for another demonstration.

Undercover informants soon tipped off the police of the Marchers’ intent.

By 11:30 A.M., Wednesday, December 21st, a caravan of unmarked vans surrounded the destitute’s base-of-operations, an ugly little hall at 10628 96th Street. The placard above its door read:

“УКР РОБІТНИЧО-ФЕРМЕРСЬКИЙ ДІМ — UKRAINIAN LABOR TEMPLE EDMONTON.”

A moment passed as R.C.M.P. Superintendent W.F.W. Hancock and E.P.D. Chief of Detectives Robertson Sutherland assessed their surroundings — the street was dead. Both got out of their vehicle, and slowly moved towards the dilapidated building.

The two picked up speed as they crossed the street. One uniformed Mountie and E.P.D. constable quickly followed. Another two did, then ten, then twenty.

Leading the cavalcade of baton-wielding policemen, Hancock and Sutherland smashed through the Temple’s doors. 400 marchers stared back. With a bark, Sutherland ordered the building cleared twenty-five men at a time. The constabulary “lined them up in front of the old church building next door,” the Journal said, “until detectives checked them over and found those they wanted.” A list of prime ‘agitators’, provided by Detective Wilchinski, acted as their guiding document.

At the neighbouring church, the Young Communist League was holding a one hundred-strong rally. Downstairs women were preparing a turkey dinner with the food graciously donated by local farmers. Ben Swanky described:

“In my case, I was just on the platform in the youth centre speaking. They came in. We halted the meeting and filed out one-by-one. I was asked at the door what my name was. I said, ‘Ben Swanky.’ They said, ‘Young Communist League? Take him away.’ They had a bunch of mad Black Mariahs [police wagons] lined up there. They took us down to the police station.”

Others were less forthcoming. Some marchers managed to escape, in spite of the dragnet around both buildings, and in several instances “fleet-footed R.C.M.P. men [had] to run half a block before they could catch their man.” The only woman detained that day, Jennie Levine, was also “the only one arrested who threatened a struggle.” She had to be forcibly wrangled into a police car by two constables.

That night thirty individuals were crammed into the cells at City Police Headquarters — the inmates kept up their spirits by singing ‘The Red Flag’ and ‘The Internationale’. The following day, both the E.P.D. and R.C.M.P. conducted further raids on flophouses surrounding Market Square as warrants issued by Magistrate Col. George B. McLeod called for the arrest of twenty more marchers. They found most soon enough.

A trial date for those marchers charged with ‘unlawful assembly’ was set for mid-January. In the intrim, the E.P.D. transferred its prisoners to the Federal Penitntiary at Fort Saskatchewan. Swanky described that “hellhole,” saying:

“It [had] small cells, about four-feet wide, about eight-feet long. There was one little twenty-watt light way up high, and one little window that barely let in any light, and a toilet and a wash basin. We were kept there for days, we weren’t allowed out to do any activity or to move our legs or anything.”

THE Fallout, Trial & Analysis

Public and professional opinion split following the March. To some the whole event was nothing more than petulant outburst from Alberta’s Left. To others, a righteous cause advancing working-class struggle. Both of Edmonton’s leading papers allied themselves with the former’s interpretation. To them, the marchers assembled, made it 140 meters, and were struck down. As the Bulletin said:

“The hunger march accomplished nothing for the reason there was nothing to accomplish. Misnamed, misplanned, mishandled, the demonstration was born of pretence and died of exposure. The marchers were not hungry and desperate, and the public knew it. That killed any chance it might have had arousing popular support.”

The Canadian Labour Defence League saw it differently. “The Alberta Hunger March marks a turning point in the history of working class struggle in Canada,” they wrote. “It marks a goal achieved. Never before in the history of this country have Farmers and Industrial Workers show such a united front as was shown in Edmonton on December 20th, 1932.”

Despite their spin, communist hardliners seethed. For them, it only solidified the C.P.C.’s view on their nominally progressive allies. Edmonton’s Labour government and Alberta’s Farmer government always went to great lengths to emphasize their proletarian character, yet neither had qualms siccing the police on their purported supporters. The C.L.D.L. condemned both:

“This is the way the ‘Socialist’ Brownlee Government and the ‘Socialist’ Labor City Council deal with workers and farmers who are desperately in need of food, clothing and shelter. ‘Socialist’ Knott watched the whole bloody affair from his window in the city hall, the Labor Bureaucracy watched from their windows in the Labor Hall.”

The Young Worker: Official Organ of the Young Communist League echoed similar sentiments. As the ruling U.F.A. had ties to the newly formed Co-operative Commonwealth Federation — an overtly socialist federal political party formed that year — they decried both as nothing more than liberals in disguise. They wrote:

“The Brownlee government has arrested and deported young Sophie Sheinin for leading an unemployment demonstration; it discriminates against radical workers who are on relief; it has sent its provincial police to terrorize, arrest, and persecute miners who were on strike in the Crow’s Nest pass. This is the Socialism of the C.C.F. to-day when it is practically in power in Alberta. This is the ‘Socialism’ we can expect from the C.C.F. if it ever gets into power in Ottawa.”[12]

This was all part of a broader movement within Communist International-aligned elements. To be anything right of communist was “social-fascist” especially in the case of Left-wing parties and organizations. Progressive allies were not to be trusted, they argued, and the March proved that to them in spades. For the next three years, the Communist Party of Canada directed most of its political capital towards attacking the C.C.F. — they only softened their view with the rise of fascism in the mid-to-late 1930s.

Whatever your politics, however, most outside of Edmonton agreed; Premier Brownlee and Mayor Knott went too far. The Winnipeg Tribune covered the event with a solemn dignity, opining that “There are two ways of handling the so-called ‘Unemployment Demonstrations’. So far as one on the outside may judge, Edmonton on Tuesday chose the poorer of the two ways.” Coverage from San Fransisco’s Examiner described the March in brutal terms, writing that “Blood flowed on the city market square today, when Royal Canadian Mounted Police, swinging riot clubs from their saddles, charged at 3,000 unemployed who were attempting to stage a hunger march.” The Texas-based Marshall News Messenger went further. “Cracked heads, bumps, and bruises were dealt out profusely to the marchers, and blood flowed freely as they fell back before the mounted police…” they wrote in an article entitled “Canada Uses Clubs To Stop Demonstration.”

Back in Edmonton, the newspapermen of the Bulletin and Journal dissected the ‘riot’ looking for its root cause. Destitution, drought, deportation of dissidents? No, said the papers, it was malicious ‘agitators’ and outside influencers. Their thoughts were part-and-parcel for the day. As Burton wrote, “For most of the Depression, politicians, businessmen, army leaders, and police had tried to pretend that ‘agitators’… were at the root of the nation’s troubles. Get rid of them… and the problem will go away.”

Indeed, nothing was wrong with the country economically, they held. Prime Minister Bennett, on vacation in England at the time of the March, said as much. With a jovial smile on his face he predicted that 1933 “will see the beginning of a new era of prosperity.” The lean years of 1930-32 were an aberration, the common line said, and in time the great chain of Capital would sort itself out. Anyone who dared think otherwise was either a radical, misguided, or, worse, ‘foreigners’.

Yes, the threat of ‘foreigners’ was a pervasive current in contemporary coverage.[13] It was those ‘outsiders’ with their ‘weird’ names who were trying to undermine Anglo-Canadian society with their strange ideology, the mainstream held. It could only be them, those Russians, Ukrainians, Finns, and Belorussians, already predisposed to socialism from their time in Europe, who were responsible. No God-fearing, King-loving, true-blooded Canadian could in their right mind be swept up in the ideals of the far-Left, they thought.[14]

The fear of ‘foreign’ agitators was such that the R.C.M.P. “made up [its] raiding squad from the Mounted Police of [the] Smokey Lake and Thorhild detachments,” as “[t]hese men, used to policing foreign settlements, knew how to cope with the large foreign gathering.”

Trials followed that January. Bill Swanky described:

“We got us our lawyer, a man by the name of House [15] who was also the head of the Liberal Party. He agreed to be our legal council, because he figured we’d discredit the U.F.A. government, then the Liberals would be elected. He did a good job too as lawyer for us. We were arrested and charged with being in an unlawful assembly... We saw a lot of perjury on the witness stand, and a lot couple of funny things happened to me. One is that while I was sitting in the audience with the other guys who were arrested, forty of us, the prosecutor said to Mike Hayduk, he was being talked about. He said to him, ‘Mike Hayduk, stand up.’ He pointed to me. I looked a bit like him. The judge said, ‘you sit down, you’re not Mike Hayduk.’ The judge intervened just when I was going to prove that they didn’t even know who they were talking about.

Like its prosecutor, the Crown’s star witness, Detective Wilchinski, proved amateurish at the stand. [16] The Journal recalled one incident during the trial when Wilchinski — after describing in detail the numerous speeches he heard — was asked to “identify certain of the defendants whom he had previously mentioned:”

“Spectators, members of the jury, and even Mr. Justice Ives laughed heartily when Wilchinski sought to pick out George Poole from the group of defendants, forming a large semi-circle at the front of the court.

The officer made the complete circuit of the group scanning each face closely, and finally pausing to give voice to the perplexed ejaculation:

‘He’s changed his face!’

‘You’re getting warmer,’ R.F. Jackson, one of the defence counsel observed as Wilchinski passed close to the table at which the lawyers and newspaper reporters were seated.

‘There he is,’ the detective declared triumphantly, pointing to a man seated next to Mr. Jackson.

‘I thought he was a lawyer and it fooled me,’ witness explained as the courtroom burst into laughter.

Poole is conducting his own self-defence.”

Ultimately, six of those brought to trial received sentencing on charges of unlawful assembly — they served their time at the Fort Saskatchewan Penitentiary. Two others, John Yager and John Yachilovich, received sentences for brandishing makeshift weapons during the brawl.

March-leaders Charles Stewart, August Popin, and Andrew Irvine — that rousing farmer-turned-communist speaker — were arrested a month later on charges of unlawful assembly. Each of the accused paid their $1,000 bail bonds thanks to the C.L.D.L., which successfully fundraised $23,000 to cover the legal fees associated with defending the marchers.

Both Irvine and Stewart were brought to trial in the Alberta Supreme Court the following November. Stewart received one year of hard labour at Fort Saskatchewan. “I will give you a chance to be a worker,” Justice Carlos Ives dryly declared. The defendant was indifferent:

“I have been arrested for things I have done in the cause of the workers before, and I have been in the movement for several years. As long as I am regarded as leader of the workers, I will expect to be arrested, convicted, and sentenced. All that I ask is those who remain shall carry on the work!”

For his part, Irvine received two months. Ives became considerably more sympathetic when the communist’s personal history, and the story of his dying mother, was revealed to the court. “I don’t regard your case in the same light as I do that of Stewart,” the judge remarked.

Some others, like twenty-five year-old John Corrigan — the eloquent speaker who had caught the attention of, and begrudging appreciation from, undercover informants — evaded capture for another year. When finally apprehended by police in June 1934, he faced identical charges. Corrigan conducted his own defence — “I may say I have been very greatly impressed by you during the course of the trial,” Justice Lunney commended. Still, Corrigan’s jury convicted him. They recommended leniency given his age.

The Communist Party martyrized each of the sentenced, and in the end came out the victor, at least temporarily. Their Hunger March became one of Canada’s first large-scale demonstrations protesting ineffectual Depression-era governance and marked, in the words of Gilbert Levine, “the biggest single manifestation of class conflict in Alberta during the entirety of the 1930s.” The March, Levine contended, “was the provincial equivalent of the On-To-Ottawa Trek of 1935. The Trek had more breadth in terms of regional and national attention but the Hunger March probably had more depth in terms of local support. It brought together some 12,000 people in a city with a population of 80,000, or about one quarter of the adult population.”

Indeed, the connection to the later On-to-Ottawa Trek is apt. The Communist Party, Canadian Labour Defence League, and Workers’ Unity League studied the successes and failures of Edmonton’s March, whose lessons they then applied to future protests, including the successful 1935 Vancouver Relief Workers’ Strike. This latter event precipitated the ill-fated Trek and, in that lineage, Edmonton’s demonstration, Fred Cleverly argued, “thereby became the indirect cause of the grand finale of the Communist insurgency in Canada.”

Cited Notes:

Andrew Irvine’s reference to “the King’s Highway” means Jasper Avenue in this context, then part of the Provincial Highway System. His use of “parliament” is in reference to the Legislature of Alberta. Although it has since fallen out of common use, the term was often applied to provincial bodies and government buildings across Canada during the era. Alberta’s Legislature Building was thus “the Alberta Parliament Building[s].”

As far as I have been able to ascertain, there is no familial relation between Andrew Irvine, the communist, and Thomas H. Irvine, the policeman. Just another one of history’s great (and confusing) coincidences.

There is some confusion over what caused the Mounties to move in. The Edmonton Bulletin asserts that Edmonton Police Department “Sergt. Maj. Dan Fraser who was assisting to hold the parade back was struck over the head with the leading parade banner.” This story is mentioned once more, in the subsequent court trial, by Sergeant Edward Watson, also of the E.P.D. The Journal recounted his testimony, saying “[a] missile, that I took for a stone, just missed a policeman and struck the side of the post-office building. We ordered the paraders to stop and then two or three of them struck the police with their fists. One was carrying a banner stick.” Conversely, the marchers paint a different picture and emphatically emphasized the rally’s civilized nature. While one may argue the protesters would defend their character, unaligned onlookers tended to agree. Clare Botsford, a nine year-old spectator, for instance, was standing near the point of conflict. When asked later-in-life if the marchers had anything to do with instigating the violence, she stated “Nothing... [It was] a peaceful crowd.” It is worth mentioning that Sergeant-Major Fraser himself was apparently not called as a witness during the subsequent inquiry and court trial. For the purposes of this essay, neither side has been depicted at particular fault.

For further discussion on the Workers’ Unity League, see Stephen Endicott’s exhaustive work, Raising the Workers’ Flag: The Workers’ Unity League of Canada, 1930-1936.

For further discussion on the Farmers’ Unity League, see David Monod’s The Agrarian Struggle: Rural Communism in Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1926-1935. Monod details that the F.U.L., originally headed by Jack Clarke, was often at odds with Moscow and the Third International. “For the communist ideologues,” Monod writes, “Clarke had committed the vital sin of reviving the ‘old opportunistic theory of the class antagonism between the proletariat and the poor farmer’ and he had further dishonoured himself by advocating debt adjustment, state credit and a minimum farm wage. This, [Stewart Smith, a leading member of the Communist Party of Canada] cautioned, was little other than ‘pink reformism.’” [Pg. 108]

For further discussion on the Alberta-chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, see William Peter Baergen’s The Ku Klux Klan in Central Alberta. In regards to their relation to Mayor D.K. Knott, the Klan threw their support behind him during his 1932 re-election bid. In part, they conducted a brutal smear campaign against Knott’s top-competitor, ex-mayor Kenneth A. Blatchford, who they repeatedly labeled “a Papist sympathizer.” Blatchford suffered a nervous breakdown and committed suicide five-months later.

Two sources — John Gilpin’s Edmonton: Gateway to the North and Ben Swanky’s oral history interview with the Alberta Labour History Institute — assert that the Edmonton Police Department and Royal Canadian Mounted Police were “reinforced by 150 constables from Regina” on December 20th. This is extremely doubtful in my mind. Excluding one mention in the Journal — itself claiming that this “could not be confirmed” — I found no period references to this fact, and extant photographs of the March reveal that there was probably no more than the established ~120 policemen present in-total. There exists a historical probability that either the E.P.D., R.C.M.P. and/or Province of Alberta solicited assistance from the Regina-area R.C.M.P. and/or Regina Police Department, but if it did it seems that their call went unanswered or they were unable to accommodate the request.

A historic region of Eastern Europe now part of present-day Ukraine. Previously part of the Austro-Hungarian, Polish, and Russian Empires.

Also “Jack,” “James,” “John James,” and “Joseph” in period sources. John seems to be the most commonly repeated of these, so was chosen here.

Patrick Lenihan, Irishman, one-time member of Sinn Féin, and well-known labour activist, is worth looking into. He ran for Calgary City Council in 1938 under the Communist Party banner and won a seat. Authorities arrested Lenihan in 1940 for his staunch anti-war stance. [Many C.P.C. members adopted similar positions following the Soviet-Nazi Pact, but that is a discussion beyond the scope of this essay.] Post-war, Lenihan entered the civil service and became instrumental in the formation of Alberta’s public-sector unions. See Gilbert Levine’s Patrick Lenihan: From Irish Rebel to Founder of Canadian Public Sector Unionism for more.

In her PhD dissertation, Proletarian Publics: Leftist and Labour Print in Canada, 1930-1939, Andrea Hasenbank provides an interesting analysis of this quotation. She writes that “[t]he narrative stands out… by centring the experience of an individual among the crowd, rather than the collective force of the marchers, or the protests and demands of an entire class. Yet, the ‘individual’ represented by the speaker is a blank, as are the location and the event, leaving ample space for a reader to project him or herself, and permitting the endless repurposing of the account for other marches and other publications. For these reasons, I would argue this narrative is the most effective element of [The Alberta Hunger-March and the Trial of the Victims of Brownlee’s Police Terror], both as pure propaganda, and as a potential organizing tool.” [Pg. 156]

The communists, though publications like The Young Worker or The Alberta Hunger-March and the Trial of the Victims of Brownlee’s Police Terror, often claimed that Premier John Brownlee was a devout socialist; he was anything but. Brownlee represented the ‘conservative’ wing of the social democratic United Farmers of Alberta government — which included his cabinet and party Éminence grise Henry Wise Wood — and actively dampened attempts put forward by the party’s sizeable socialist caucus — which included the backbenchers, publishers of the party’s official publication, The U.F.A., and Party President Robert Gardiner — to move leftward during the Depression. The communists’ oft-cited link between the United Farmers and newly-formed Co-operative Commonwealth Federation was tenuous because of this. The U.F.A.’s conservative wing had difficulties reconciling their moderate politics with the unabashedly socialist character of the C.C.F. While the two parties became formally affiliated following the Co-operatives’ founding in August 1932, and whilst the U.F.A.’s socialist caucus advocated for further integration between them, some, like Wood, feared the Co-operatives subsumption of the Farmers entirely.

References to ‘foreign’ agitation was both overt and passive. Although a more brazen quote is included here, it is also worth underlining the innocuous. The December 19th Edmonton Bulletin article “Demonstrations By ‘Hunger Army’ Will Be Prevented Here,” for instance, provides a good example of the latter: “Investigations have revealed that 231 men came in from Northern Alberta points on Sunday, mostly of the non-English speaking type. They were put into quarters at the Ukrainian Temple on 96 Street.” [Underlining mine.] Invariably, the press’ continued emphasis on “non-English speaking” Canadians flooding their city aimed to inspire a fear of socialism and communism in their predominantly Anglo-Canadian audience and insinuate, by extension, that far-Left politics naturally had to be an import from outside agitators.

The press and political establishment’s emphasis on socialism’s ‘foreign’ — i.e. un-British — nature is particularly humorous in retrospect when one considers that Canada’s leading socialists — such as J.S. Woodsworth, William Irvine, Angus MacInnis, Agnes MacPhail, Robert Gardiner and others — were either born-in Great Britain, raised by British parents, or were educated in the English-tradition of Fabianism. Most were staunch anti-communists. Tim Buck, Communist Party of Canada leader, meanwhile, was an Englishman by birth.

Swanky almost certainly meant “Howson” not “House.” William Robinson Howson was, at the time, a sitting Member of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta and recently appointed leader of the Liberal Party of Alberta. A lawyer by trade, he later became a judge for the Alberta Supreme Court.

Per Hasenbank: “Based on sources including census data, voters’ lists, and the Henderson’s Directory for Edmonton, there seems to be some evidence that [Detective Wilchinski] was using the name Andrew Wilkie between 1932 and 1945, reappearing as Wilchinski post-1945.” [Pg. 163.] Hasenbank posits that Wilchinski may have changed his name to avoid the post-March scorn of communist-aligned elements in Edmonton. While there are occasional references to “Wilchinski” in subsequent Edmonton Bulletin and Journal reporting — see the Journal’s October 24th, 1934 article, “Girl In Daze After 4 Days,” as one-such example — they become fewer and further between.

Sources:

News / Print Media:

“Jobless Delegates Stranded in City,” Edmonton Journal, March 3, 1932.

“Grand Scramble In Words, Questions In Police Court,” Edmonton Journal, May 5, 1932.

“Mounted Police Will Have Horses,” Edmonton Journal, June 20, 1932.

“Two Marchers Facing Trial In High Court,” Edmonton Bulletin, November 8, 1933.

“Plea Made To Allow Idle In Hunger March,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 1, 1932.

“Destitute Youth of Alta. Join Hunger March on Edmonton,” The Young Worker: Official Organ of the Young Communist League of Canada, December 2, 1932.

“Hunger Marchers Voicing Protests,” Edmonton Journal, December 5, 1932.

“The Inquiring Reporter,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 5, 1932.

“Orders Are Given With Directness Near to Military,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 5, 1932.

“Hunger March Banned Here,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 9, 1932.

“The March,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 10, 1932.

“Challenge of Hunger Army Draws Fire,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 13, 1932.

“Hunger Marchers Are Determined To Stage Parade,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 14, 1932.

“Superintendent Acland Transferred to Regina,” Edmonton Journal, December 16, 1932.

“Hunger Marchers Arriving Monday,” Edmonton Journal, December 19, 1932.

“Demonstrations By ‘Hunger Army’ Will Be Prevented Here,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 19, 1932.

“Propaganda Brought Farmers To City To Join ‘Hunger March,’” Edmonton Bulletin, December 20, 1932.

“Blood Flows as R.C.M.P. And City Officers Enforce Government Ban on Parade,” Edmonton Journal, December 20, 1932.

“Brownlee Hears Marchers’ Claims,” Edmonton Journal, December 21, 1932.

“Police Raid Headquarters, Charge Unlawful Assembly; Believe New Meet Blocked,” Edmonton Journal, December 21, 1932.

“Police Crush ‘Hunger March’ Here,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 21, 1932.

“Rioters Lose Out As Officers Use Batons In Crowd,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 21, 1932.

“New ‘Hunger’ Disturbance Nipped Here,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 21, 1932.

“Bennett Sails From England For New York,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 21, 1932.

“The Edmonton Demonstration,” Winnipeg Tribune, December 21, 1932.

“Canadian Jobless Clubbed by Police,” San Francisco Examiner, December 21, 1932.

“Canada Uses Clubs to Stop Demonstration,” Marshall News Messenger, December 21, 1932.

“Warning Issued By Brownlee Against Radical Outbreaks,” Calgary Herald, December 21, 1932.

“Alleged ‘Red’ Chiefs Caught In Police Net,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 22, 1932.

“Warning For Hunger Marchers In Alberta,” The Blairmore Enterprise, December 22, 1932.

“Local and General Items,” The Blairmore Enterprise, December 22, 1932.

“Deny Red Orders Seized in Raids,” Edmonton Journal, December 23, 1932.

“Brutal Beatings, Arrests of Alta. Hunger Marcher (sic),” The Young Worker: Official Organ of the Young Communist League of Canada, January 11, 1933.

“The Young People’s Socialist League, the Young Labor Federation, and the Young Communist League,” The Young Worker: Official Organ of the Young Communist League of Canada, January 11, 1933.

“Police Court,” Edmonton Bulletin, February 17, 1933.

“Hunger Marchers Facing Trial,” Edmonton Bulletin, November 6, 1933.

“Stewart Given Year In Jail On Riot Count,” Edmonton Bulletin, November 9, 1933.

“Serve Old Warrant Hunger Marcher,” Edmonton Journal, June 16, 1934.

“Remand Corrigan for Trial Unlawful Assembly Count,” Edmonton Journal, June 25, 1934.

“City Sleuth Admits ‘Red’ Orator Good,” Edmonton Bulletin, October 10, 1934.

“Accuse Corrigan Of Inciting March,” Edmonton Journal, October 10, 1934.

“John Corrigan Sent to Prison,” Edmonton Journal, October 11, 1934.

“Early Crimes Recalled: Tributes Paid Two Retiring Veteran City Detectives,” Edmonton Journal, January 5, 1948.

Eugene W. Plawiuk, “The Great Edmonton Hunger March of 1932,” The Boyle-McCauley News, February 1993.

Gordon Kent, “Don’t Be So Smug Canucks,” Edmonton Journal, March 20, 1994.

Contemporary Reports & Documents:

Library & Archives of Canada, Personnel Records of the First World War, Irvine, Andrew, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 4709 - 69,

https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?op=pdf&app=CEF&id=B4709-S069.

The Alberta Hunger-March and the Trial of the Victims of Brownlee’s Police Terror: A Document to All Workers and Farmers to Remember the Events of December 20th, 1932 (Edmonton, AB: Canadian Labour Defence League: Hunger March Defence Committee, 1933), 4, 5-6, 14, 15, 18, 25, 30,

R.C.M.P. Security Bulletins, No. 713, July 4, 1934 (Ottawa, ON: Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 1934), 109,

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/RCMP/article/view/9384.

R.C.M.P. Security Bulletins, No. 728, October 17, 1934 (Ottawa, ON: Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 1934), 339,

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/RCMP/article/view/9399/9454.

R.C.M.P. Security Bulletins, No. 729, October 24, 1934 (Ottawa, ON: Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 1934), 350.

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/RCMP/article/view/9400.

Academic Papers, Journals & Oral History Interviews:

Anne B. Woywitka, “Recollections of a Union Man,” Alberta History, Vol. 23, No.4 (Autumn), 1975, 16,

http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/9021.23.4/18.html?qid=peelbib%7CCommunist%7C%7Cscore.

Jaroslav Petryshyn, A.E. Smith and the Canadian Labour Defense League (PhD diss, University of Western Ontario, February 1977), 107, 149, 152, 154.

David Monod, “The Agrarian Struggle: Rural Communism in Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1926-1935,” Historie sociale / Social History Vol. XVIII, No.35, May 1985, 107, 108.

Gordon Hak, “The Communists and the Unemployed in the Prince George District, 1930-1935,” BC Studies, No. 68, Winter 1985-86, 45.

Patricia Mazepa, Battles on the Cultural Front: The (De)Labouring of Culture in Canada, 1914-1944 (PhD diss, Carleton University, May 2003), 88, 89, 90, 91.

Ben Swanky, oral history interview by Winston Gereluk, Alberta Labour History Institute, July 2003, 5, 6, 7.

https://albertalabourhistory.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Swanky.pdf.

Andrea Grace Hasenbank, Proletarian Publics: Leftist and Labour Print in Canada, 1930-1939 (PhD diss, University of Alberta, 2019),

https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/4d1404e9-d93e-4883-a072-fe2d5b0e3d99

Alberta Labour History Institute, “ALHI - Clare Botsford - Edmonton Hunger March,” May 12, 2022, educational video, 3:05,

Books:

H. Blair Neatby, The Politics of Chaos: Canada in the Thirties (Toronto, ON: MacMillan of Canada, 1972), 24.

Norman Penner, The Canadian Left: A Critical Analysis (Scarborough, ON: Prentice-Hall of Canada Ltd., 1977), 134, 214.

Warren Caragata, Alberta Labour [Toronton, ON.: James Lorimer & Co., 1979] 102, 104, 105, 106.

John F. Gilpin, Edmonton: Gateway to the North: An Illustrated History (?: Windsor Publications Ltd., 1984), 154.

Lorne Brown When Freedom Was Lost: The Unemployed, the Agitator, and the State (Montréal, QC: Black Rose Books, 1987), 19, 25, 26.

Pierre Burton, The Great Depression: 1929-1939 (Toronto, ON: Penguin Books, 1990), XVIII, 7, 38, 76, 77, 143, 200, 202, 357.

A.J. Mair, E.P.S. The First 100 Years: A History of the Edmonton Police Service (Edmonton AB: Edmonton Police Service, 1992) 59.

Fred Cleverly, “As the Depression pain deepens, Communism launches its revolution” in Alberta in the 20th Century: Volume VI (1930-35): Fury and Futility: The Onset of the Great Depression, ed. Ted Byfield (Edmonton, AB: United Western Communications Ltd., 1998), 70, 72.

Fred Cleverly, “As Communism turns to violence, its first big riot hits Edmonton,” in Alberta in the 20th Century: Volume VI (1930-35): Fury and Futility: The Onset of the Great Depression, ed. Ted Byfield (Edmonton, AB: United Western Communications Ltd., 1998), 87, 88, 90, 94, 95.

Gilbert Levine, ed., Patrick Lenihan: From Irish Rebel to Founder of Canadian Public Sector Unionism (St. John’s, NF: Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1998), 64-65.

Kathryn Chase Merrett, A History of the Edmonton City Market, 1900-2000: Urban Values and Urban Culture (Calgary, University of Calgary Press, 2001), 80.

Bill Waiser, All Hell Can’t Stop Us: The On-to-Ottawa Trek and Regina Riot (Calgary: Fifth Hose Ltd., 2003), 18, 19.

Stephen Lyon Endicott, Raising the Workers’ Flag: The Workers’ Unity League of Canada, 1930-1936 (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 206.

Alvin Finkle, Working People In Alberta: A History (Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press, 2012), 97,

Eric Strikwerda, Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929-39 (Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press, 2013), 47, 87.

Photographic Collections & References:

McDermid Studios, photographer. “Unemployment demonstration, Edmonton, Alberta.” Photographs. Edmonton. McDermid Studios, December 1932. From Glenbow Archives, NC-6-13014A-J: McDermid Studio Fonds.

“Ukrainian Labour Temple Association temple in Edmonton, Alberta.” Photograph. Edmonton. Photographer Unknown, 1924. From Glenbow Archives, NA-2513-4.