The Second Latta Ravine Bridge

Jasper Avenue at 92nd Street

Engineer: A.W. Haddow of the City Engineering Dept.

Constructed: 1936

Demolished: 2022

David Gilliland Latta, blacksmith, one-time Royal North-West Mounted Police constable, gold rush hopeful, and City Alderman, built the first bridge over this inconsequential ravine in 1911. His handiwork was a crude thing. Wood-timber construction throughout, the small span, no more than twenty-one feet wide and off centred from Jasper Avenue, groaned under stress. But that was alright. It was a temporary bridge, a crossing never intended to handle more than the odd streetcar or horse-and-cart. For two decades his creation held, if barely.

Growing automobile ownership, heavier vehicles, and increased transit frequency wreaked havoc in the intervening years, and in 1929 traffic engineers condemned Latta’s old bridge. Yet a replacement never came, as the onset of the Great Depression prevented the City from pursuing such a finically onerous project. Some proposed a ravine-fill as an alternative — they abandoned that plan when old coal mines were discovered under the site. So, 1929 turned into 1930, and 1930 into ‘31 and ‘32. Each year the Depression’s grip grew tighter, and each year the City had to assuage fears over the bridge’s continually worsening state. Edmontonians didn’t buy it, least of all the Street Railway Department — that year they diverted their streetcars off the crossing and around its small gulch.

By the waning months of 1935, City Council could no longer ignore the trestle’s state, yet, no money was budgeted for its successor. So they advanced a clever scheme. Normally the approval of unbudgeted expenses — and the loans required to finance them — went to public plebiscite, but Council had a different idea. By law, the City had the authorization to spend up to $100,000 a year for works related to unemployment relief, if Council so directed. That November they did, proposing a new bridge as a $44,000 make-work project for Edmonton’s starving labourers.

Eric Strikwerda’s tome, Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39, writes that “the economic, political, and social benefits of work relief projects underwritten in part by federal and provincial funding were not lost on the city officials in charge of relief works” and many municipalities “consequently tried to squeeze as many items as possible related to their projects into the tripartite work relief agreements.”

The Board of Public Utilities Commissioners approved Council’s plan on December 5th, 1935, which meant that they could replace the trestle “without reference to the burgesses in form of a money bylaw.” Council formally approved the project on December 9th. Their motion, moved by Alderman Hugh MacDonald, read:

“Having considered Commissioners Report No.1 Section 8, we recommend that the work be authorized and that the necessary legal steps be taken to prepare for the letting of a contract for the Latta Ravine Bridge so that details may be completed before the expiry of the year 1935.”

Council received two tenders for “the supply, fabrication and erection of the steel work, in connection with the new bridge at Latta Ravine” on January 13th, 1936. Both the Canadian Bridge Company and Dominion Bridge Company vied for the contract. The latter won out with a bid of $25,266.25, an estimate $2015 cheaper than their competitor — neither’s proposal included costs associated with deconstruction of the old span, done instead by the City's unemployed relief workers.

Work started in March 1936 with the trestle’s dismantling. The Edmonton Journal described it as “[g]roaning and creaking under the impact of sledge hammers and crow bars that had no regard for years of service far beyond the normal span of wooden bridges.” By early April nothing was left, and the reliefers turned to pouring concrete foundations. “Of 12 inches in diameter, the 108 holes bored for this purpose extend six to seven feet deep, said City Engineer Haddow. There are nine holes under each of the 12 footings which are nine feet in diameter and extend from five feet to 15 feet below the ground surface.” Dominion Bridge took over the site on April 27th.

Jane Gibson cites Latta Bridge as “an early example of recycling of industrial materials” thanks in part to its use of upcycled components. Steel members produced for, but unused in, a 1931 modification to the High Level Bridge were “altered at a storage site and hauled to the [new] bridge by tractor,” while old streetcar tracks, hoarded by a Depression-conscious municipal government, “were also used to reinforce all mats in pedestals.” In all, seven of Latta’s nine main girders, and ninety of its total two-hundred tonnes were reused material.

As with their work on the Kinnaird Ravine Bridge, the Dominion Bridge Co. employed union tradesmen to supervise the City’s unemployed workers. While reliefers were paid “in accordance with the federal rate schedule for Edmonton District” — pegged at 48 cents per hour — they received half of what their unionized overseers made, despite the dangers associated with their work. Nevertheless, they persisted, and by May 20th had completed steel construction. “Riveting and painting [were] being rushed,” as street grading, paving, and landscaping continued into the following month. City officials soon set an opening date of June 20th, 1936.

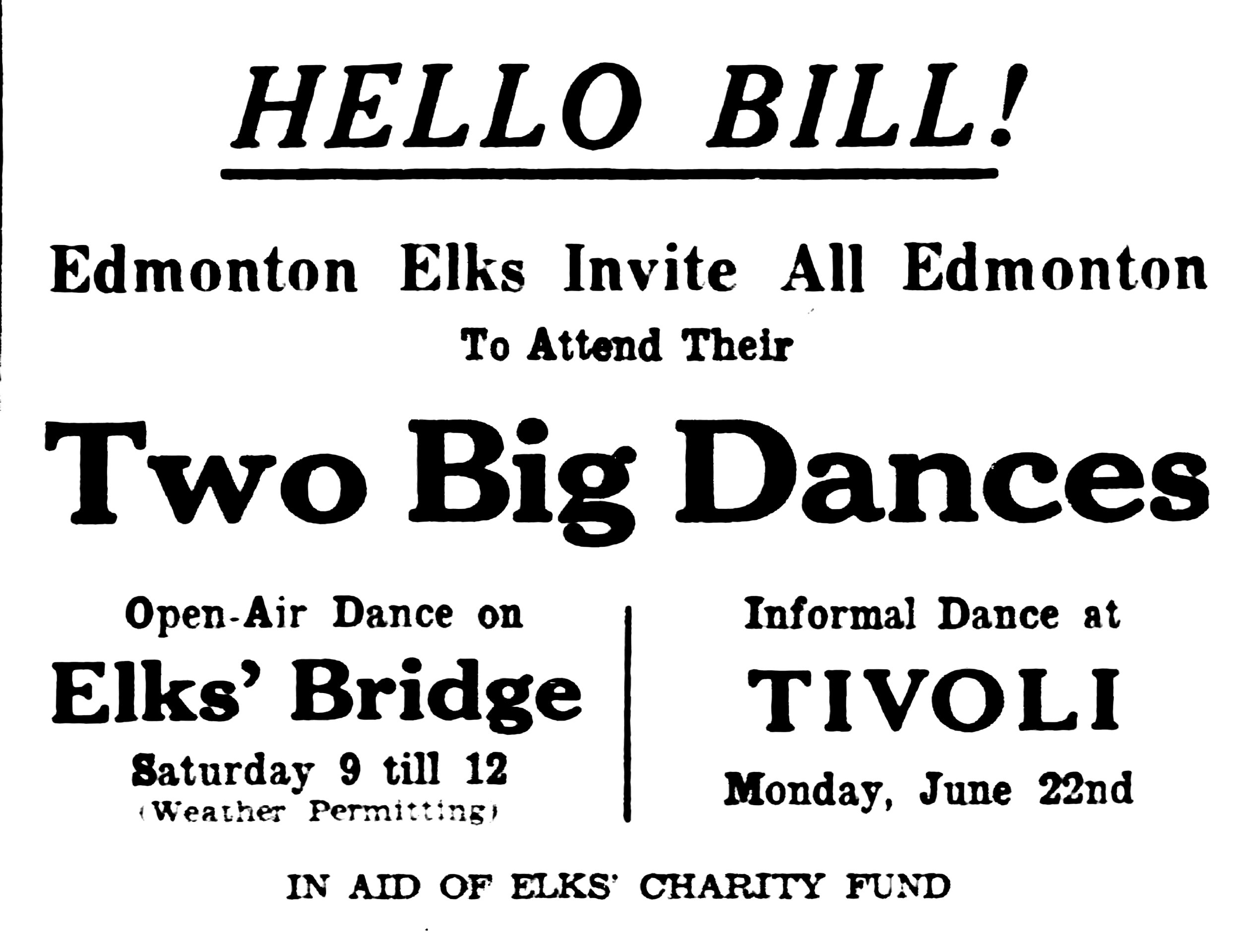

To celebrate the Bridge’s completion, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, in conjunction with the City, organized a late-night, open-air dance. Coloured lights, flags, and bunting was “especially installed for the occasion.” At 9:00 pm that Saturday, Latta Bridge welcomed Edmontonians for the first time. Couples jived to the “rhythmic strains” of the 49th Battalion’s fifteen-piece regimental band as “cars lined Jasper avenue for blocks and a big crowd filled the edges of the Latta ravine.” Of the “gaily decorated” bridge, the Journal said it “made an excellent ballroom for the many dancers, [with] green foliage and the winding river forming an impressive background.” More than two thousand people are estimated to have attended — motor traffic crossed for the first time early the following morning.

Eighty-six years later that bridge, a relic of those hard years, once lauded, “now requires replacement to maintain safe operation,” the City of Edmonton contends. Starting in August 2022, workers will dissect it beam by beam and rivet by rivet, to finally discard the material saved nearly a century prior. When the gulch is cleared, a new bridge — Latta the Third — will rise to take its place. Bigger, better, bolder, this heir promises to be an improvement for autos and pedestrians alike, with wider roads and multi-use trails. A concrete deck and stainless handrails will replace the salvaged tram tracks and leaded paint — clean and inoffensive as most modern bridges are. And maybe that's why it's hard for this author to shake a feeling of melancholy. Latta the Third will be a worthy successor, no doubt, but with it comes a lament for the gangliness of its predecessor, and the awkward, utilitarian charm that only a cash-strapped city, relief workers, and recycled material could conjure up.

Yet, plans call for one piece to be reclaimed — a bronze tablet, Edmonton's third-ever historical marker — preserving a tradition of reuse. Mayor William Hawrelak presented it to the Latta family in 1952. The plaque, a small token to the man who started it all, and a link to connect three bridges, simply reads:

“City of Edmonton Archives and Landmarks Committee. Latta Bridge. Named in honour of David Gilliland Latta, Pioneer. Edmonton Businessman, 1897-1948. Alderman, Second Council, 1906.”

Image Gallery:

Sources:

“Open Bridge For Traffic, Sunday, May 1,” Edmonton Bulletin, April 29, 1932.

“City Is Authorized To Build New $44,000 Latta Bridge Without Ratepayers’ Vote,” Edmonton Journal, December 6, 1932.

“City Receives Board Permit Latta Bridge,” Edmonton Bulletin, December 6, 1935.

“Latta Ravine Bridge,” Meeting No.3, Edmonton City Council Meeting Minutes, December 9, 1935, 4, City of Edmonton Archives,

“Two Offer Tenders For Latta Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, January 9, 1936.

“Tenders Latta Ravine Bridge,” Meeting No.8, Edmonton City Council Meeting Minutes, January 13, 1936, 9, City of Edmonton Archives,

“Latta Bridge Goes,” Edmonton Journal, March 23, 1936.

“Pouring Concrete For Latta Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, April 4, 1936.

“Bridge Footings Nearly Completed,” Edmonton Journal, April 24, 1936.

“Bridge Frame Ready,” Edmonton Journal, May 14, 1936.

“Work Is Being Rushed On Two Bridges,” Edmonton Journal, May 23, 1936.

“When Elks Bridge Was Opened,” Edmonton Bulletin, June 22, 1936.

“Thousands Join Dance on Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, June 22, 1936.

“Sees Subsidizing On City Contracts,” Edmonton Journal, June 27, 1936.

“Plaque Unveiled on Latta Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, May 29th, 1952.

“David G. Latta,” Alberta Inventors and Innovations: A Century of Innovation, accessed July 2, 2022

Jane Gibson, “The History of the Latta Bridge,” Edmonton City As Museum, June 21, 2016,

https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2016/06/21/the-history-of-the-latta-bridge/.

Colin Hatcher & Tom Schwarzkopf, Edmonton’s Electric Transit: The Story of Edmonton’s Streetcars and Trolley Buses (Toronto: Railfare Enterprises, 1983), 103.

Ken Tingly, Ride of the Century: The Story of the Edmonton Transit System (Edmonton: City of Edmonton, 2011), 100.

Eric Strikwerda, Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929-39 (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2013), 121.