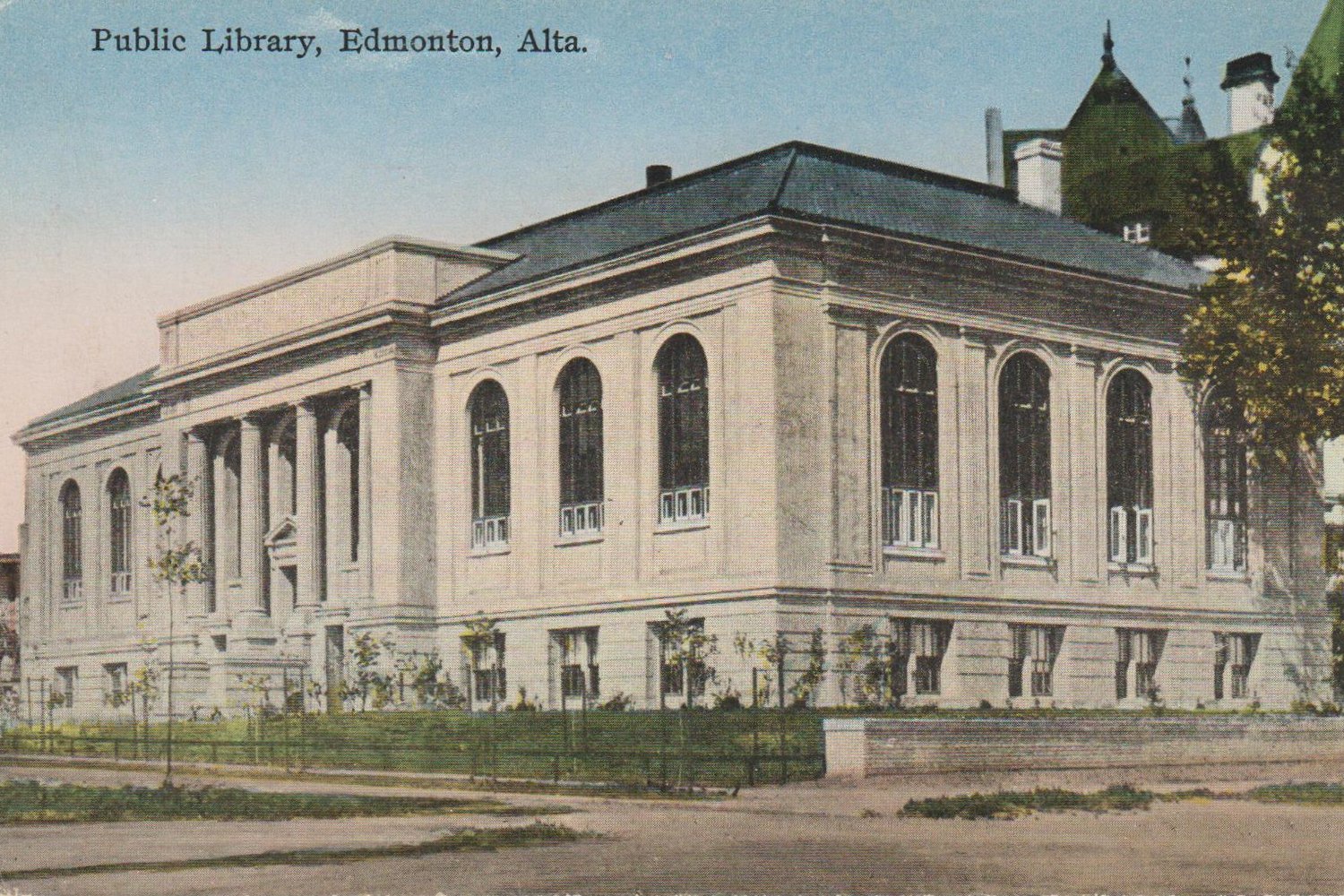

The Carnegie Library

MacDonald Drive at 100th Street

Architects: MacDonald & Magoon w/ Esther Hill

Constructed: 1922-23

Demolished: 1968

Edmonton wanted a library. Desperately.

By the time 1912 rolled around, the city’s crusade to build one had been ongoing for three years. All they had to show for it was an undeveloped lot. The slow progress might have been bearable had it not been for other developments around Alberta. Strathcona, Edmonton’s recently amalgamated southside neighbours, had managed to finance the construction of their own library despite a population of only 5,500. Calgary, meanwhile, opened their own to much fanfare that January, and Lethbridge had introduced legislation the year prior laying the foundation for their own system. Edmonton, as provincial capital, the thinking went, should have something nicer than all of them. Something grand, something central — not southside, like the new Strathcona Branch would be.

The Edmonton Public Library Board had written to the Carnegie Corporation of New York in 1911 seeking financial aid in their endeavour. While the steel magnate’s philanthropic organization had provided millions to build hundreds of libraries across North America, they were less charitable in Edmonton's case. As Todd Babiak explains in Just Getting Started: Edmonton Public Library’s First 100 Years:

“Edmonton was by far the larger city and the provincial capital. They had secured land across the street from what would be one of the finest hotels in Canada, the Hotel MacDonald. The provincial legislature was nearing completion. So was the High Level Bridge — the Carnegie Corporation offered $60,000… [The Public Library] wanted a building worth $200,000 and weren’t keen on forgoing control for less than half the price.”

Far short of their lofty expectation, the E.P.L. flatly rejected the offer, and, perhaps in an act of spite towards the New York office, were “of the opinion that further negotiations with Mr. Carnegie be dropped.” In the interim, Edmonton’s Central Branch sat on the second floor of the Chisholm Block, above a liquor store and meat shop.

With the real-estate market bottoming out and the Great War beginning, the Public Library was left in a bind. Every passing year Edmonton’s population continued to drop and with it the city’s new dream of building a library financed by Edmontonians for Edmontonians became increasingly unattainable. That didn’t disturb Ethelbert Lincoln Hill, the E.P.L.’s Chief Librarian, however. He’d always seen Edmonton as worthy of a proper library and would do his damndest to make it a reality — even if that meant returning to the Carnegie Corporation on hands and knees.

Although contact had been maintained on-and-off since 1917, Hill and other board members formally restarted their conversation with New York in 1921. While the Carnegie Foundation ceased providing library funding that year, the E.P.L. hoped the charity would make an exception. James Bertram of the Manhattan Office wasn’t completely opposed, despite the fact that it broke the Foundation’s rules. Edmonton had reversed its war-time woes, and was now growing at a reasonable clip in spite of its sluggish post-war economy. Hill’s persistence also impressed Bertram. In January 1922, he invited a delegation, consisting of Mayor David M. Duggan and library board chair L.T. Barclay, to woo him in person. It worked. When the two returned they proudly announced that Edmonton was getting its library, on the condition the City could provide an additional $37,000 — an emergency bylaw approved the sum that April.

The only stipulations given by the foundation was that the new building must be “oblong in form, comprising one storey and high basement, with lantern lighting, to be built in stone and brick and conforming as nearly as may be to the elevations of the library erected by the City of Washington D.C.” Otherwise, they gave the City and Library Board free rein. It was an unusual arrangement as the Carnegie Corporation had, at one point, been notorious for their fickleness. Babiak writes that while “it was normal for [them] to spend some time with plans, to debate and criticize them, to find errors and outright abominations where designers and library boards found none,” they did no such thing for Edmonton. The library perched atop the Saskatchewan bluffs was to be their last — they wanted it over with.

It was a blessing for the City. They could build the library of their dreams, and commissioned local architectural firm MacDonald & Magoon to do just that. The duo of George H. MacDonald and Herbert A. Magoon couldn’t have been a better choice. By 1922 they had already left a lasting impression on Edmonton’s built form with their thoughtful, conservative plans. As Lawrence Herzog wrote, their partnership “became synonymous with good design and attention to detail and, even in frontier times, they made sophisticated use of stylistic influences from eastern Canada, America and Europe.” Joining them was their protégé, Esther Marjorie Hill, Canada’s second female architecture graduate and daughter of the E.P.L.’s Chief Librarian. In 1925 she became Canada’s first registered female architect.

A contemporary issue of the Edmonton Bulletin described the three’s plan:

“The idea, says G.H. MacDonald… consists of a more elastic style of building in which the fixed partitions, which so far have been used in the interior of libraries, are discontinued, and their place taken by a main library room.

The theory is, says the architect, that silence is observed in all the rooms of a library, therefore why the need of dividing them up by partitions? The dividing is done by the book stands, and as need increases, so the number of stands can be added to.

The library building consists of two stories and a basement.

The main floor is above the ground floor and is one large room with a ceiling of 22ft. high. It contains the librarian’s office and connected with it are two offices for assistance, vault, and elevator. Reading room space is in the south-east end overlooking the attractive view of the river valley…”

Librarian Hill, describing the building in a piece for the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal, continued:

“Messrs. MacDonald and Magoon, the architects, designed a building that has wonderfully well fulfilled the wishes of the Board and the librarian. The attractive and dignified appearance of the building speaks for itself. It cannot be too strongly emphasized that the adaptation of the building to its needs has not been sacrificed to appearance. This is a virtue all too rare in public buildings which frequently follow the whims of the civic powers in defiance of the sound advice of competent architects…

In an appropriate place in the main reading room is a Caen stone panel executed by Major Norbury, a sculptor of wide experience, showing the profile of the great builder of public libraries, and bearing as an inscription this sentence from Mr. Carnegie’s address delivered upon the opening of the Carnegie Institute: ‘The Taste for Reading is one of the Most Precious Possessions of Life.’”

Edmonton’s Carnegie Library opened to large crowds at both the afternoon and evening ceremonies on August 30th, 1923. Premier Herbert Greenfield and Mayor Duggan inaugurated the new building formally at 3:00 p.m. “This was a great pleasure stated the premier in view of the fact that institutions of this kind mean so much for the intellectual development of the people.” Duggan concurred, saying that “the general representation of all sections, classes and creeds that were present at the opening testified very plainly… that the library was filling the needs of all citizens.” Tea followed and a band played all afternoon.

The Carnegie went on to serve valiantly for three decades, but by the early '60s change was afoot. When MacDonald, Magoon, and Hill designed it, Edmonton was home to 60,000. Since then the city had quintupled in size, and the building was being pushed well beyond its intended capacity and role. Compounding matters was Chief Librarian Morton Coburn. A modernist in every sense, he wanted “contemporary books, contemporary architecture, contemporary librarians, and a contemporary system.” In his mind the old Carnegie Library was an aging anachronism not fit for purpose.

With help from local philanthropist Stanley Milner, Corburn pursued a campaign to replace Edmonton’s acropolis, and in 1965 the City and Library Board agreed that the construction of a new central library would become its principal Centennial project. When the new Centennial Branch opened in 1967, the Carnegie’s death notice came. The jubilant spirits surrounding Canada’s hundredth birthday likely softened the blow. As historian Tony Cashman recalled, “I don’t remember anyone complaining at the time. People were quite excited about the new library in the square. It certainly wasn’t controversial.” Indeed, one Journal columnist summed up the thoughts of most when he opined that “the old place will be missed. It gave much reading pleasure to many and we acknowledge the debt. However, there is no denying that its facilities were overtaxed by a growing Edmonton, and we can all take pride in its handsome successor.”

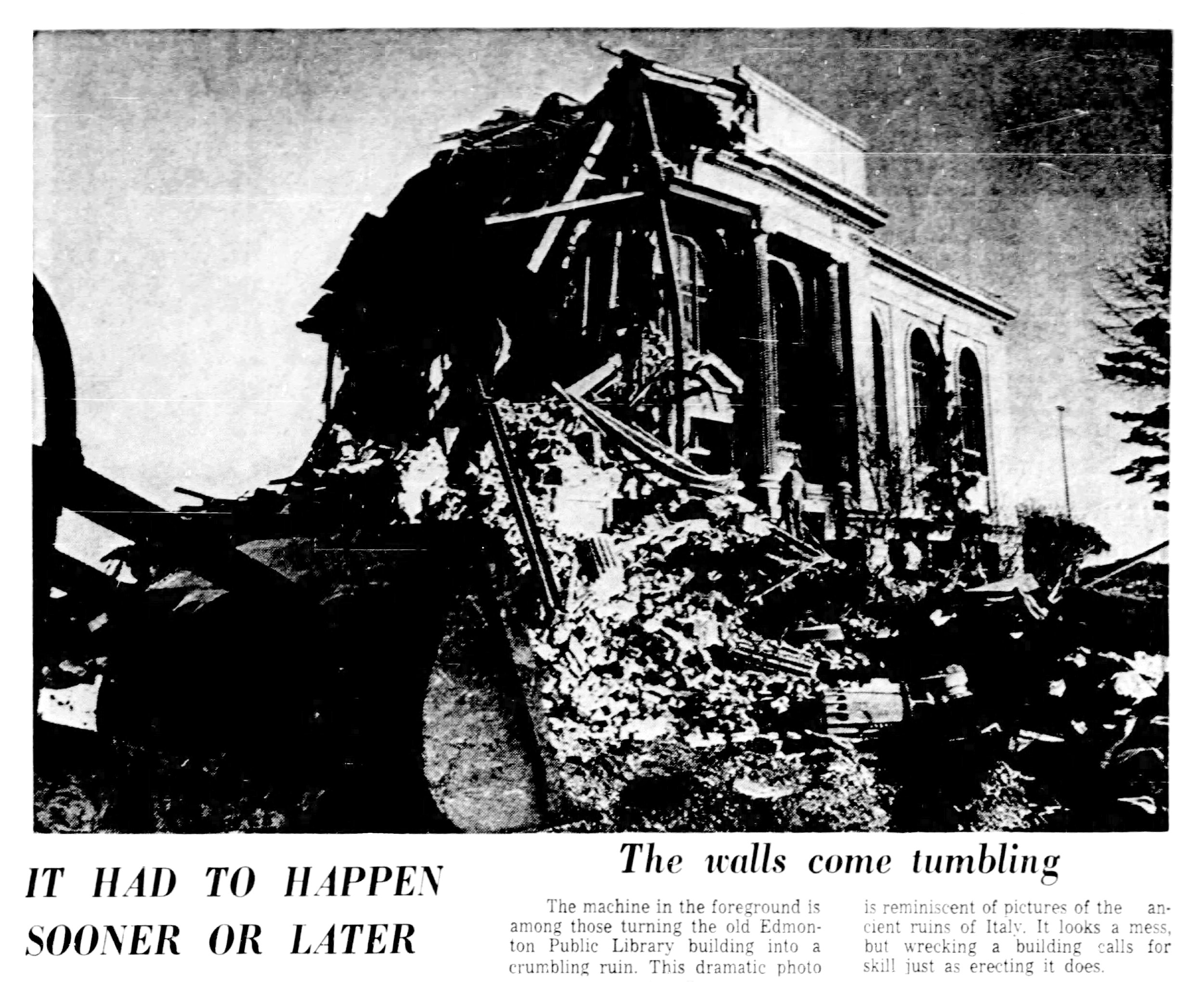

The City awarded Poole Construction — the library’s builder forty-six years prior — the contract for the Carnegie’s destruction, and demolition commenced in August 1968. Work lasted nearly three months. It turns out the ol’ building was made of sterner stuff then most. “It was no pushover,” Art Evans eulogized:

“The process seemed painfully slow to passerby who had made good use of the library for many years and in doing so developed an affection for the building itself. When it comes time for old friends to go down, buildings or people, we prefer a quick ending. But the library lingered on as though reluctant to leave the scene without a struggle.

It’s a relief the battle is over. One can now emerge from the Macdonald hotel and look across the street without wincing.”

Image Gallery:

Sources:

“City Asked To Vote Funds For New Library,” Edmonton Journal, April 7, 1922.

“Good Progress By Contractors At New Library,” Edmonton Journal, September 22, 1922.

“Progressive City of Canadian West: City Has Two Public Libraries,” Edmonton Journal, September 26, 1922.

“Building in Course of Erection Provides For Future Extension,” Edmonton Bulletin, September 26, 1922.

“New Library Is Officially Open: Opening Ceremonies Draw Large Crowds at Both the Afternoon, Night Meetings,” Edmonton Bulletin, August 31, 1923.

“Ceremonies Mark Formal Opening of New Library,” Edmonton Journal, August 31, 1923.

E.L. Hill, B.A., M.Sc., “Edmonton Public Library”, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal Vol.3, No.4 (1926), 155-156

Art Evans, "Big Book Push,” Edmonton Journal, June 10, 1967.

Art Evans, “Stiff Resistance,” Edmonton Journal, October 16, 1968.

Percy Johnston, “George Heath MacDonald (Class of 1911): The Story of One Graduate from McGill University's School of Architecture,” Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada Journal Vol.21, No.3 (1996) 74-76,

“Hill, Esther Marjorie,” Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada: 1800-1950, accessed March 29, 2022,

“Herbert Alton Magoon” Edmonton’s Architectural Heritage, accessed March 30, 2022,

https://www.edmontonsarchitecturalheritage.ca/architects/herbert-alton-magoon/.

Todd Babiak, Just Getting Started: Edmonton Public Library’s First 100 Years, 1913-2013 (Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta Press & Edmonton Public Library, 2013)